By Isel Cuapio

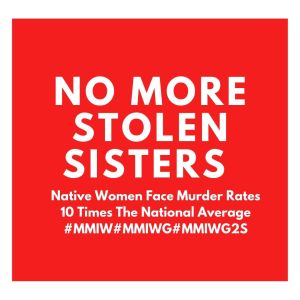

Native women and girls go missing at higher rates than any other group in this country. Violence rates against women and girls on Native American reservations are ten times higher than the national average. According to the American Psychological Association, homicide is the third leading cause of death among Native girls and women aged 10 to 24, and the fifth leading cause of death for Native women aged 25 to 34. Unfortunately, we may never learn the names of these girls and women and we may never know their story. However, what we can do is bring awareness to the issue to end this epidemic of extreme violence. On Wednesday, September 11, 2019, tribal leaders across Indian Country along with Congress hosted the 25th anniversary of the Violence Against Women Act. Since its enactment in 1995, VAWA has been reauthorized in 2000 and 2005 to expand and improve efforts. The Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2019 passed the House on a 263 to 158 vote in April and is still yet to be taken to the Senate for a vote. Rep. Deb Haaland, Laguna Pueblo, D-New Mexico, said that the Senate needs to be pressured to vote on the bill because “the safety of our women depends on it.” Though some progress has been made, continued challenges still exist in tracking and reporting cases of missing and murdered indigenous women and girls.

Earlier in the morning on the day of the 25th anniversary of VAWA, there was also a subcommittee hearing reviewing the Trump administration’s approach to the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) crisis. Representatives testified on behalf of the Department of Health and Human Services and the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The testimonies outlined the psychological impacts and long term consequences of all forms of violence against children. These long term effects and consequences include changes to mental and physical developments, learning disorders, and a continued cycle of violence over generations. They also outlined some of the current challenges in gathering data on crimes and improving efforts on cooperating with federal, state and tribal officials. Though national systems such as Amber Alert, Tribal Access Program (TAP) and NamUS were implemented in tribal communities to better track missing women and girls, representatives mentioned that these efforts had already been in place and wanted to see more of a breakthrough in these efforts. Bureau of Indian Affairs representative Charles Addington said that while there are wide gaps in reported data and a lack of people working in law enforcement surrounding reservations, more outreach efforts have been made to inform tribal communities and local and federal enforcement on appropriate procedures to report missing person cases. Often, cases are never reported, which is why very little data exists to track murdered and missing person cases. After the hearing, lawmakers concluded that if there is insufficient progress, they would provide more oversight on these federal agencies. Though the move towards more oversight isn’t a bad idea, in order to truly move forward, as Representative Deb Haaland says we need to call on the Senate to take action. We cannot continue to live in a world where native women and girls continue to go missing. We must urge the Senate to take immediate action, as an end to this crisis is necessary, now that it has caused a great deal of pain and terror in tribal communities.

To learn more information about Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women or to donate, please visit the links below:

National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls